Last Updated: October 28, 2025 | Reading Time: 50 minutes

Quick Answer: What is the difference between strong and weak acids?

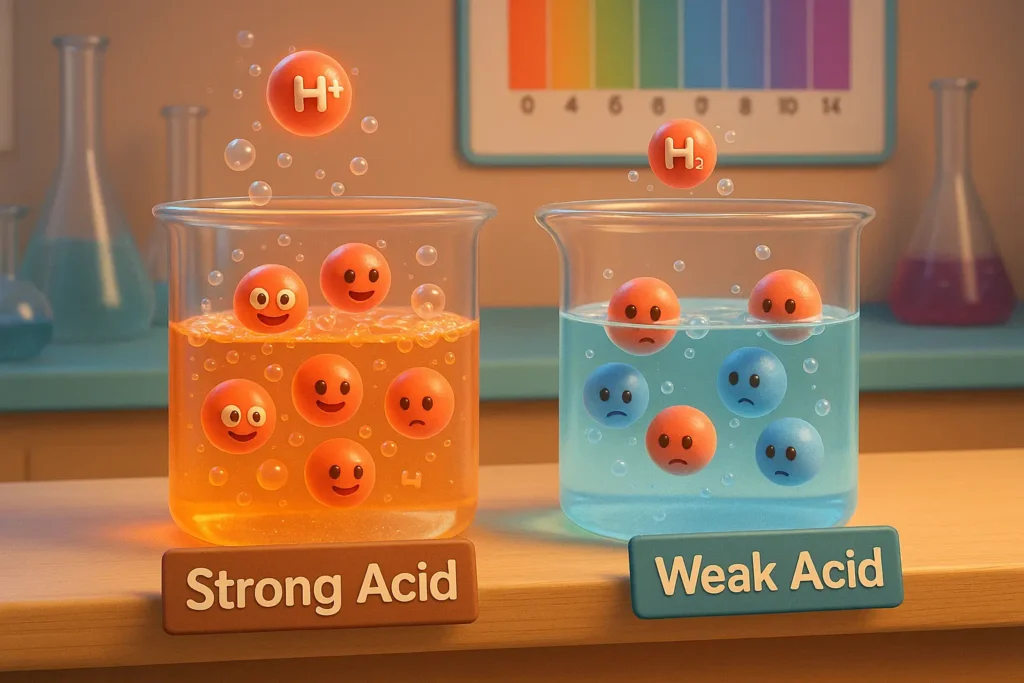

Strong acids completely dissociate (100% ionization) in water, releasing all their hydrogen ions, while weak acids only partially dissociate (typically 1-10% ionization), maintaining equilibrium between ionized and molecular forms.

The seven strong acids are: HCl, HBr, HI, HNO₃, H₂SO₄, HClO₃, and HClO₄. All other acids are classified as weak acids, including common examples like acetic acid (vinegar), citric acid (citrus fruits), and carbonic acid (carbonated beverages).

Key Difference in One Sentence: A 0.1 M solution of hydrochloric acid (strong) has pH 1.0, while a 0.1 M solution of acetic acid (weak) has pH 2.9—nearly 100 times less acidic despite identical concentrations.

Table of Contents

What Are Strong and Weak Acids?

Understanding the fundamental difference between strong and weak acids is crucial for chemistry students, laboratory professionals, industrial chemists, and anyone working with acidic solutions.

Definition of Strong Acids

Strong acids are chemical substances that undergo complete dissociation (100% ionization) when dissolved in water. This means every single acid molecule breaks apart into hydrogen ions (H⁺ or H₃O⁺) and their corresponding anions. The reaction proceeds entirely to completion with no reverse reaction.

Chemical Representation: HA(aq) → H⁺(aq) + A⁻(aq) [100% completion, irreversible]

Example: Hydrochloric Acid HCl(aq) → H⁺(aq) + Cl⁻(aq)

When you dissolve 1 mole of HCl in water, you get exactly 1 mole of H⁺ ions and 1 mole of Cl⁻ ions. Zero HCl molecules remain intact in solution.

Key Characteristics:

- Complete ionization (100%)

- No equilibrium state

- Very high Ka values (often >10³)

- Very low or negative pKa values (typically <0)

- All molecules converted to ions

- Represented with single arrow (→)

- Only seven common strong acids exist

Visual Representation: Before dissolution: 100 HCl molecules After dissolution: 0 HCl molecules, 100 H⁺ ions, 100 Cl⁻ ions Ionization: 100%

Weak Acids: The Partial Ionizers

Weak acids are chemical substances that only partially dissociate in aqueous solutions, establishing a dynamic equilibrium between the molecular form and ionized form. At any given moment, most acid molecules remain intact, with only a small percentage donating protons.

Chemical Representation: HA(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + A⁻(aq) [Partial equilibrium, reversible]

Example: Acetic Acid CH₃COOH(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + CH₃COO⁻(aq)

When you dissolve 1 mole of acetic acid in water, only about 0.01-0.05 moles actually dissociate into ions. The remaining 0.95-0.99 moles stay as intact CH₃COOH molecules.

Key Characteristics:

- Partial ionization (typically 1-10%)

- Equilibrium established

- Low Ka values (typically 10⁻² to 10⁻¹⁵)

- Positive pKa values (typically 1-15)

- Majority of molecules remain intact

- Represented with double arrow (⇌)

- Thousands of weak acids exist

Visual Representation: Before dissolution: 100 CH₃COOH molecules After equilibrium: 95 CH₃COOH molecules, 5 H⁺ ions, 5 CH₃COO⁻ ions Ionization: 5%

The Ionization Percentage

The percentage of acid molecules that dissociate determines acid strength:

| Acid Type | Ionization % | Ka Range | pKa Range | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | ~100% | > 10³ | < 0 | HCl, H₂SO₄ |

| Moderately Weak | 10–50% | 10⁻¹ to 10⁻² | 1–2 | H₃PO₄ |

| Weak | 1–10% | 10⁻² to 10⁻⁵ | 2–5 | Formic acid |

| Very Weak | 0.1–1% | 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻¹⁰ | 5–10 | Acetic acid |

| Extremely Weak | < 0.1% | < 10⁻¹⁰ | > 10 | Phenol, Water |

Why This Distinction Matters

The complete versus partial ionization creates profound differences that affect:

1. Chemical Properties:

- pH levels at equivalent concentrations (1-3 pH unit difference)

- Reaction rates with metals, bases, and carbonates (10-100× difference)

- Electrical conductivity (100× difference)

- Buffering capacity (weak acids buffer, strong acids don’t)

2. Biological Systems:

- Blood pH regulation (requires weak acid buffers)

- Enzyme function (pH-dependent activity)

- Drug absorption (ionization affects membrane permeability)

- Metabolic processes (weak acid intermediates)

3. Industrial Applications:

- Process selection (strong for speed, weak for control)

- Safety requirements (strong acids 15× more injuries)

- Cost considerations (5-10× higher safety costs for strong acids)

- Environmental impact (strong acids cause severe damage)

4. Practical Skills:

- pH calculations (simple for strong, complex for weak)

- Acid identification (conductivity, reaction rate tests)

- Buffer preparation (only weak acids work)

- Titration procedures (different indicators needed)

Common Misconceptions

MYTH #1: “Strong acids are more dangerous than weak acids.” TRUTH: Strength refers to ionization, not danger. Hydrofluoric acid (HF) is a weak acid but extremely dangerous, causing deep tissue damage and bone destruction. Always respect all acids regardless of classification.

MYTH #2: “Concentrated weak acids are stronger than dilute strong acids.” TRUTH: Concentration and strength are different. A concentrated weak acid has more molecules but still low ionization. A dilute strong acid has fewer molecules but 100% ionization. 1 M acetic acid (weak, concentrated) has pH ~2.4, while 0.01 M HCl (strong, dilute) has pH 2.0 (more acidic).

MYTH #3: “Weak acids can become strong acids if concentrated enough.” TRUTH: Acid strength is an inherent molecular property that cannot change with concentration. Acetic acid remains a weak acid whether it’s 0.001 M or pure (17 M). The percentage ionization decreases with concentration, but it never reaches 100%.

MYTH #4: “There are many strong acids.” TRUTH: Only seven acids are commonly classified as strong. All others—numbering in the thousands—are weak acids. This makes strong acid identification easy: if it’s not one of the seven, it’s weak.

The Seven Strong Acids You Must Know

There are only seven commonly recognized strong acids. If an acid isn’t on this list, it’s classified as a weak acid, regardless of how strong it may seem.

Memory Tip: “Some Strong Acids Have Incredible Nasty Power Certainly”

- Sulfuric (H₂SO₄)

- Strong (reminder)

- Acids (reminder)

- Hydrochloric (HCl)

- Hydroiodic (HI)

- Hydrobromic (HBr)

- Nitric (HNO₃)

- Perchloric (HClO₄)

- Chloric (HClO₃)

1. Hydrochloric Acid (HCl)

Formula: HCl Molecular Weight: 36.46 g/mol pKa: Approximately -7 (extremely acidic) Physical State: Gas at room temperature; commercial form is aqueous solution

Molecular Structure: Simple diatomic molecule: H-Cl bond Bond length: 127 pm Highly polar covalent bond

Complete Dissociation: HCl(aq) → H⁺(aq) + Cl⁻(aq) [100%]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Clear, colorless liquid (aqueous solution)

- Odor: Pungent, sharp, irritating

- Density: 1.18 g/cm³ (37% solution)

- Boiling Point: -85°C (pure gas), ~110°C (20% solution)

- Completely miscible with water

- Fumes in moist air (forms HCl mist)

Key Applications:

1. Human Digestion (Stomach Acid):

- Concentration in stomach: 0.16 M (pH 0.8-1.5)

- Production: 1.5-2.0 liters daily

- Functions: Kills pathogens (99.9% bacteria), activates pepsinogen to pepsin, denatures proteins, solubilizes minerals (Ca²⁺, Fe²⁺)

- Protection: Mucus layer prevents self-digestion

- Disorders: GERD (excess acid), achlorhydria (insufficient acid)

2. Steel Pickling and Metal Treatment:

- Removes oxide scales and rust from steel surfaces

- Concentration: 10-18% HCl at 50-70°C

- Reaction: Fe₂O₃ + 6HCl → 2FeCl₃ + 3H₂O

- Scale: 8 million tonnes HCl used annually for pickling

- Benefits: Fast (minutes), thorough, economical

3. pH Control (Swimming Pools, Water Treatment):

- Lowers pH and total alkalinity

- Typical dosage: 100-500 mL per 10,000 gallons

- Advantages: Fast-acting, no residue, economical

- Safety concern: Handling requires care

4. Chemical Production:

- Organic chlorides synthesis

- Inorganic chemicals (metal chlorides)

- PVC plastic production (chlorine source)

- Pharmaceutical intermediates

5. Food Processing:

- Corn syrup production (starch hydrolysis)

- Gelatin manufacturing

- Food-grade HCl for pH adjustment (rare, strictly regulated)

Global Production:

- Annual production: 20+ million tonnes

- Market value: £15 billion

- Major producers: USA, China, Germany, India

- Production method: Salt + Sulfuric acid, or Chlorine + Hydrogen

Safety Information:

- Classification: Corrosive, causes severe burns

- Exposure limits: TWA 2 ppm (ceiling 5 ppm)

- PPE required: Goggles, face shield, acid-resistant gloves, lab coat

- First aid: Flush with water 15+ minutes, seek immediate medical attention

- Storage: Corrosion-resistant containers, separated from bases and metals

2. Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄)

Formula: H₂SO₄ Molecular Weight: 98.08 g/mol pKa₁: Approximately -3 (first dissociation, strong) pKa₂: 1.99 (second dissociation, weak) Physical State: Dense, oily liquid

Molecular Structure: Central sulfur atom bonded to 4 oxygen atoms (tetrahedral geometry) Two O-H bonds (acidic hydrogens) Two S=O double bonds Bond angles: ~109.5°

Complete First Dissociation: H₂SO₄(aq) → H⁺(aq) + HSO₄⁻(aq) [100%, strong] HSO₄⁻(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + SO₄²⁻(aq) [Partial, weak, Ka = 1.2 × 10⁻²]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Clear, colorless, odorless liquid (pure)

- Density: 1.84 g/cm³ (98% concentrated)

- Viscosity: Highly viscous, oily consistency

- Boiling Point: 337°C (decomposes)

- Melting Point: 10°C (pure acid)

- Hygroscopic: Absorbs moisture from air

- Exothermic dilution: Releases tremendous heat

Unique Properties:

1. Dehydrating Agent: Removes water from substances, charring organic materials

- Dehydrates sugar: C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁ → 12C + 11H₂O (black carbon tower)

- Dries gases in laboratory procedures

- Industrial drying applications

2. Oxidizing Agent: Concentrated hot H₂SO₄ oxidizes metals and non-metals

- Reacts with copper: Cu + 2H₂SO₄(conc, hot) → CuSO₄ + SO₂ + 2H₂O

Key Applications:

1. Lead-Acid Batteries (Largest Single Use):

- Battery acid concentration: 30-35% H₂SO₄

- Function: Electrolyte for electron transfer

- Discharge: Pb + PbO₂ + 2H₂SO₄ → 2PbSO₄ + 2H₂O

- Charge: Reverse reaction

- Market: 280 million car batteries annually

- H₂SO₄ consumption: 50 million tonnes/year

- Advantage: High ionic conductivity, low cost, recyclable (95%+ recycling rate)

2. Fertilizer Production (65% of Total H₂SO₄ Use):

- Phosphate rock treatment: Ca₃(PO₄)₂ + 3H₂SO₄ → 2H₃PO₄ + 3CaSO₄

- Ammonium sulfate production: 2NH₃ + H₂SO₄ → (NH₄)₂SO₄

- Scale: 180 million tonnes H₂SO₄ annually

- Impact: Feeds 3+ billion people globally

- Economic value: £25 billion

3. Petroleum Refining:

- Alkylation catalyst (produces high-octane gasoline)

- Removes sulfur impurities

- Lubricating oil production

- Consumption: 15 million tonnes/year

4. Chemical Manufacturing:

- Produces hundreds of chemicals

- Examples: Titanium dioxide (TiO₂ pigment), rayon fibers, detergents, explosives

- Industrial significance: “Backbone of chemical industry”

- Economic indicator: H₂SO₄ production correlates with industrial development

5. Metal Processing:

- Steel pickling and cleaning

- Copper ore leaching

- Metal surface treatment

- Electroplating preparation

6. Wastewater Treatment:

- pH adjustment (neutralizes alkaline water)

- Metals precipitation

- Large-scale municipal plants

Global Production:

- Annual production: 280+ million tonnes (world’s most produced chemical)

- Market value: £50+ billion

- Major producers: China (70 million tonnes), USA (40 million tonnes), India (15 million tonnes)

- Production method: Contact process (S + O₂ → SO₂ → SO₃ + H₂O → H₂SO₄)

Safety Information:

- Classification: Extremely corrosive and dangerous

- Concentrated acid causes instant severe burns

- Dilution hazard: ALWAYS add acid to water (exothermic reaction)

- Adding water to acid causes violent boiling and spattering (dangerous!)

- Exposure limits: TWA 1 mg/m³

- PPE: Full face shield, acid-resistant suit, heavy-duty gloves

- First aid: Continuous water flush 30+ minutes, immediate emergency medical care

- Famous safety phrase: “Do like you oughta, add acid to water”

3. Nitric Acid (HNO₃)

Formula: HNO₃ Molecular Weight: 63.01 g/mol pKa: Approximately -1.4 Physical State: Liquid

Molecular Structure: Central nitrogen with three oxygen atoms (trigonal planar) One O-H bond (acidic hydrogen) Two N=O bonds (resonance structures) Bond angle: ~120°

Complete Dissociation: HNO₃(aq) → H⁺(aq) + NO₃⁻(aq) [100%]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Colorless when pure, yellow/brown when decomposed (NO₂ present)

- Odor: Acrid, suffocating

- Density: 1.51 g/cm³ (70% solution)

- Boiling Point: 83°C (68% solution)

- Fuming: Concentrated acid releases NO₂ vapors

- Light-sensitive: Decomposes to NO₂ (turns yellow)

- Decomposition: 4HNO₃ → 4NO₂ + O₂ + 2H₂O

Unique Property – Powerful Oxidizer: Reacts with most metals, even relatively unreactive ones

- Copper: 3Cu + 8HNO₃(dilute) → 3Cu(NO₃)₂ + 2NO + 4H₂O

- Copper: Cu + 4HNO₃(conc) → Cu(NO₃)₂ + 2NO₂ + 2H₂O

- Silver: Dissolves silver (used in silver recovery)

- Passive metals: Forms protective oxide layer on aluminum, iron (passivation)

Xanthoproteic Reaction: Stains proteins yellow (diagnostic test)

- Skin contact: Yellow staining appears after exposure

- Permanent until skin cells shed

Key Applications:

1. Fertilizer Production (80% of HNO₃ Use):

- Ammonium nitrate: NH₃ + HNO₃ → NH₄NO₃

- Calcium ammonium nitrate: Mixed fertilizer

- Scale: 50 million tonnes HNO₃ for fertilizers

- Impact: Essential for global food production

- Nitrogen content: 34% N in NH₄NO₃ (high efficiency)

2. Explosives Manufacturing:

- TNT (trinitrotoluene): Toluene + 3HNO₃ → TNT + 3H₂O

- Nitroglycerin: Glycerin + 3HNO₃ → Nitroglycerin + 3H₂O

- RDX, PETN, and other military explosives

- Safety: Extremely hazardous synthesis requires expertise

- Historical: Enabled modern explosives industry (1860s+)

3. Rocket Propellants:

- Oxidizer in liquid rocket fuel

- Examples: Red fuming nitric acid (RFNA), white fuming nitric acid (WFNA)

- Space applications: Titan missiles, Apollo program

- Current: Still used in some military applications

4. Metal Etching and Passivation:

- Stainless steel passivation (removes free iron, forms protective Cr₂O₃ layer)

- Semiconductor manufacturing (etches silicon)

- Printed circuit boards (copper etching)

- Artistic metalwork (decorative etching)

5. Organic Synthesis:

- Nitration reactions (introduce -NO₂ groups)

- Polyurethane precursors

- Dyes and pigments

- Pharmaceutical intermediates

6. Analytical Chemistry:

- Digestion of samples for metal analysis

- Aqua regia component (HCl + HNO₃, dissolves gold and platinum)

- Oxidizing agent in chemical analysis

Global Production:

- Annual production: 60+ million tonnes

- Market value: £30 billion

- Major producers: China, USA, Russia, Germany

- Production method: Ostwald process (NH₃ + O₂ → NO → NO₂ + H₂O → HNO₃)

Safety Information:

- Classification: Corrosive, oxidizer, toxic

- Produces toxic nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) gas

- Exposure limits: TWA 2 ppm, STEL 4 ppm

- Health hazards: Respiratory damage, chemical burns, pulmonary edema (delayed)

- PPE: Goggles, face shield, acid-resistant gloves, fume hood mandatory

- Ventilation: Excellent ventilation required at all times

- Incompatibilities: Never mix with organic materials (fire/explosion risk)

- Storage: Brown bottles (light-sensitive), cool storage

- First aid: Water flush 15+ minutes, immediate medical attention, monitor for delayed respiratory effects

4. Hydrobromic Acid (HBr)

Formula: HBr Molecular Weight: 80.91 g/mol pKa: Approximately -9 (one of the strongest acids) Physical State: Gas; commercial form is aqueous solution

Molecular Structure: Simple diatomic molecule: H-Br bond Bond length: 141 pm (longer than H-Cl) Polar covalent bond (less polar than HCl)

Complete Dissociation: HBr(aq) → H⁺(aq) + Br⁻(aq) [100%]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Colorless to light yellow liquid (aqueous)

- Odor: Pungent, acrid

- Density: 1.49 g/cm³ (48% solution)

- Boiling Point: -66°C (pure gas)

- Fumes in moist air

- More acidic than HCl (weaker H-Br bond)

Key Applications:

1. Pharmaceutical Synthesis:

- Organic bromide intermediates

- Alkyl bromide production

- Drug manufacturing (brominated compounds)

- Examples: Sedatives, anticonvulsants, analgesics

- Market: High-value pharmaceutical intermediates

2. Organic Chemistry:

- Cleaves ethers: R-O-R’ + HBr → R-Br + R’-OH

- Converts alcohols to bromides: R-OH + HBr → R-Br + H₂O

- Addition to alkenes: C=C + HBr → C-C-Br (Markovnikov’s rule)

- Laboratory reagent for functional group transformations

3. Catalysis:

- Acid catalyst in organic reactions

- Alkylation reactions

- Esterification catalyst

4. Analytical Chemistry:

- Titrations and standardizations

- Determination of unsaturation in organic compounds

- Research applications

Global Production:

- Annual production: <1 million tonnes (specialty chemical)

- Market value: £500 million

- Produced: On-demand or small-scale industrial

- Production method: H₂ + Br₂ → 2HBr, or NaBr + H₂SO₄

Safety Information:

- Classification: Corrosive, causes severe burns

- Similar hazards to HCl but less common

- Exposure limits: TWA 3 ppm

- PPE: Same as HCl (goggles, gloves, lab coat)

- Storage: Corrosion-resistant containers, cool, dark

- First aid: Water flush 15+ minutes, medical attention

5. Hydroiodic Acid (HI)

Formula: HI Molecular Weight: 127.91 g/mol pKa: Approximately -10 (strongest hydrohalic acid) Physical State: Gas; commercial form is aqueous solution

Molecular Structure: Simple diatomic molecule: H-I bond Bond length: 161 pm (longest H-X bond) Weakest H-I bond = strongest acid

Complete Dissociation: HI(aq) → H⁺(aq) + I⁻(aq) [100%]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Colorless when freshly prepared, darkens on exposure (iodine formation)

- Odor: Sharp, penetrating

- Density: 1.70 g/cm³ (57% solution)

- Boiling Point: -35°C (pure gas)

- Unstable: Light and air cause decomposition to I₂

- Strongest common aqueous acid

Decomposition: 4HI + O₂ → 2I₂ + 2H₂O (turns solution brown/purple from iodine)

Unique Property – Excellent Reducing Agent: Unlike other hydrohalic acids, HI readily reduces other substances

- Reduces sulfur: H₂SO₄ + 8HI → H₂S + 4I₂ + 4H₂O

- Reduces Fe³⁺: 2Fe³⁺ + 2I⁻ → 2Fe²⁺ + I₂

Key Applications:

1. Organic Synthesis:

- Cleaves ethers (most powerful, works at room temperature)

- Williamson ether cleavage: R-O-R’ + HI → R-I + R’-OH

- Alcohol to iodide conversion: R-OH + HI → R-I + H₂O

- Iodination of aromatic compounds

2. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing:

- Synthesis of iodinated organic compounds

- Drug intermediates requiring iodine incorporation

- Preparation of iodine-containing medications

- Veterinary pharmaceuticals

3. Analytical Chemistry:

- Reducing agent in chemical analysis

- Carius method for halogen determination

- Research applications

4. Disinfectants:

- Source of iodine for antimicrobial applications

- Iodophor production

5. Acetic Acid Production (Historical):

- Monsanto process catalyst (now replaced by rhodium catalysts)

- Historical significance in industrial chemistry

Global Production:

- Annual production: <0.5 million tonnes (specialty chemical)

- Market value: £300 million

- Produced: Primarily on-demand due to instability

- Production method: I₂ + H₂S → 2HI + S, or KI + H₃PO₄

Safety Information:

- Classification: Corrosive, causes severe burns

- Light-sensitive: Store in dark bottles

- Air-sensitive: Use fresh solutions

- Exposure limits: TWA 0.1 ppm (ceiling)

- PPE: Goggles, face shield, acid-resistant gloves

- Storage: Dark bottles, inert atmosphere (N₂), refrigerated

- First aid: Water flush 15+ minutes, immediate medical attention

6. Perchloric Acid (HClO₄)

Formula: HClO₄ Molecular Weight: 100.46 g/mol pKa: Approximately -10 (one of strongest known acids) Physical State: Liquid (unstable in pure form)

Molecular Structure: Central chlorine with four oxygen atoms (tetrahedral) One O-H bond (acidic hydrogen) Three Cl=O bonds Highly oxidized chlorine (+7 oxidation state)

Complete Dissociation: HClO₄(aq) → H⁺(aq) + ClO₄⁻(aq) [100%]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Colorless liquid (70% solution, commercial form)

- Odor: Odorless (pure), acrid if decomposing

- Density: 1.77 g/cm³ (72% solution)

- Unstable: Pure acid (>72%) extremely dangerous, explosive

- Hygroscopic: Absorbs moisture from air

Extreme Oxidizing Power: Most powerful oxidizer among common acids

- Organic materials: Spontaneous combustion/explosion risk

- Reducing agents: Violent reactions

- Metals: Rapid oxidation

- Safety critical: Requires specialized handling protocols

Key Applications:

1. Analytical Chemistry (Primary Use):

- Volumetric analysis (standardized titrant)

- Perchlorate salt preparation (highly soluble, useful in gravimetric analysis)

- Electrolyte in electrochemistry

- Ion chromatography eluent

2. Electropolishing:

- Stainless steel surface finishing

- Removes microscopic imperfections

- Produces mirror-like surfaces

- Applications: Medical devices, aerospace components, semiconductor equipment

- Process: Electrolytic removal of surface atoms in HClO₄/CH₃COOH bath

3. Rocket Propellants:

- Ammonium perchlorate (NH₄ClO₄) = solid rocket fuel oxidizer

- Production: NH₃ + HClO₄ → NH₄ClO₄

- Applications: Space Shuttle boosters, military missiles, fireworks

- Advantage: High oxygen content, stable storage

4. Perchlorate Salt Production:

- Sodium perchlorate: NaOH + HClO₄→ NaClO₄ + H₂O

- Potassium perchlorate: KOH + HClO₄ → KClO₄ + H₂O

- Uses: Explosives, pyrotechnics, airbag inflators, analytical standards

5. Metal Digestion:

- Sample preparation for trace metal analysis

- Completely dissolves organic matrices

- ICP-MS and ICP-OES sample prep

Global Production:

- Annual production: <100,000 tonnes (specialized chemical)

- Market value: £200 million

- Highly regulated due to explosion hazards

- Production method: Electrolysis of chloric acid or sodium chlorate

Critical Safety Information:

- Classification: EXTREMELY HAZARDOUS – Corrosive and powerful oxidizer

- Explosion risk: Pure acid (>72%) can explode spontaneously

- Organic contact: Can cause immediate fire or explosion

- Never use with: Wood, paper, fabric, organic solvents, reducing agents

- Fume hoods: MUST be specially designed for perchloric acid (wash-down systems)

- Wooden fume hoods: FORBIDDEN for HClO₄ use

- Spills: Extreme danger – evacuate, call hazmat team

- Storage: Only dilute solutions (<70%), glass containers, isolated from all organic materials

- Disposal: Professional hazmat disposal only

- Training: Mandatory specialized training before handling

- PPE: Full face shield, chemical-resistant suit, heavy neoprene gloves, safety shower immediately available

- First aid: Massive water flushing, immediate emergency medical care, potential for delayed explosive reactions in tissue

OSHA Requirements:

- Dedicated perchloric acid hoods required

- Quarterly hood inspections and washdowns mandatory

- Written standard operating procedures

- Personal monitoring for exposure

- Emergency response plans

7. Chloric Acid (HClO₃)

Formula: HClO₃ Molecular Weight: 84.46 g/mol pKa: Approximately -3 Physical State: Exists only in aqueous solution (never isolated pure)

Molecular Structure: Central chlorine with three oxygen atoms One O-H bond (acidic hydrogen) Two Cl=O bonds Chlorine in +5 oxidation state

Complete Dissociation: HClO₃(aq) → H⁺(aq) + ClO₃⁻(aq) [100%]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Colorless solution

- Stability: Decomposes in concentrated form

- Cannot be isolated: Pure acid extremely unstable

- Maximum concentration: ~30% in water

- Powerful oxidizer

Decomposition: 3HClO₃ → 2ClO₂ + HClO₄ + H₂O 8HClO₃ → 4Cl₂ + 3O₂ + 4H₂O

Key Applications:

1. Chlorate Salt Production:

- Sodium chlorate: NaOH + HClO₃ → NaClO₃ + H₂O

- Potassium chlorate: KOH + HClO₃ → KClO₃ + H₂O

- Uses: Bleaching agent, herbicide, oxidizer in matches and fireworks

2. Laboratory Reagent:

- Generated in situ for specific reactions

- Oxidizing agent in organic synthesis

- Not stored, prepared as needed

3. Bleaching (Historical):

- Paper industry bleaching (now replaced by chlorine dioxide)

- Textile whitening (historical use)

4. Research Applications:

- Preparative chemistry

- Study of oxidation mechanisms

- Academic research only

Global Production:

- Limited direct production (unstable)

- Chlorates produced via electrolysis of brine, then acidified as needed

- Rarely handled as free acid

- Market: Primarily chlorate salts (£1 billion market)

Safety Information:

- Classification: Corrosive and strong oxidizer

- Stability: Unstable in concentrated form

- Explosion risk: With organic materials and reducing agents

- Exposure limits: Not well-established (rarely encountered)

- PPE: Goggles, face shield, acid-resistant gloves, lab coat

- Handling: Generate small quantities as needed, use immediately

- Storage: Not stored pure; chlorate salts stored separately from acids

- First aid: Water flush 15+ minutes, medical attention

Quick Reference Comparison Table

| Acid Name | Formula | pKa | Strength Rank | Primary Use | Production (tonnes/yr) | Safety Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroiodic | HI | -10 | 1 (strongest) | Organic synthesis | < 0.5 M | High |

| Perchloric | HClO₄ | -10 | 1 (strongest) | Analytical chemistry | < 0.1 M | EXTREME |

| Hydrobromic | HBr | -9 | 3 | Pharmaceuticals | < 1 M | High |

| Hydrochloric | HCl | -7.4 | 4 | Steel pickling | 20 M | High |

| Chloric | HClO₃ | -3.5 | 6 | Laboratory | Minimal | High |

| Sulfuric | H₂SO₄ | -3.5 | 6 | Fertilizers | 280 M | EXTREME |

| Nitric | HNO₃ | -1.47 | 7 | Fertilizers | 60 M | High |

Note: H₂SO₄ only first dissociation is strong; second dissociation is weak (Ka₂ = 1.2 × 10⁻²)

Common Weak Acids and Their Applications

Unlike the limited list of strong acids, thousands of weak acids exist in nature and industry. Here are the most important ones you should know.

Acetic Acid (CH₃COOH) – The Most Important Weak Acid

Formula: CH₃COOH or C₂H₄O₂ Common Name: Ethanoic acid Ka: 1.8 × 10⁻⁵ pKa: 4.76 Molecular Weight: 60.05 g/mol

Molecular Structure: Carboxylic acid functional group (-COOH) Methyl group (CH₃) attached to carboxyl group Planar geometry around carboxyl carbon

Partial Dissociation: CH₃COOH(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + CH₃COO⁻(aq) [~1.3% at 0.1 M]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Clear, colorless liquid

- Odor: Characteristic vinegar smell (pungent, sour)

- Density: 1.049 g/cm³ (pure)

- Boiling Point: 118°C

- Melting Point: 16.6°C (freezes in cold weather = “glacial acetic acid”)

- Miscible with water in all proportions

- Corrosive: Attacks skin, but much less severe than strong acids

Common Form: Vinegar

- Concentration: 4-8% acetic acid (typically 5%)

- pH: Approximately 2.4 (5% vinegar)

- Production: Fermentation of ethanol by Acetobacter bacteria

- Types: White vinegar (distilled), apple cider vinegar, wine vinegar, balsamic vinegar

- Historical: Used for 10,000+ years (ancient preservation method)

Applications:

1. Food Preservation and Pickling (Largest Consumer Use):

- Inhibits bacterial growth (pH below 4.5 prevents Clostridium botulinum)

- Mechanism: Undissociated acid form penetrates bacterial membranes, disrupts internal pH

- Effectiveness: 99.999% pathogen reduction at 2-5% concentration

- Products: Pickles, sauerkraut, chutneys, sauces, marinades

- Shelf life extension: 300-500% increase

- Flavor: Provides tartness and preserves color

- Consumer preference: “Clean label” – natural preservation method

- Market growth: 15% annually (vs declining synthetic preservatives)

2. Household Cleaning:

- Concentration: 5-10% for cleaning applications

- Uses: Glass cleaner, deodorizer, descaler (removes hard water deposits), fabric softener, mold remover

- Advantages: Non-toxic, biodegradable, safe for food contact surfaces

- Effectiveness: Kills 99% of bacteria, 80-82% of molds, 99.9% of viruses

- Cost: £1-2 per liter (economical)

- Environmental: Completely biodegrades in 24-48 hours

3. Chemical Manufacturing:

- Vinyl acetate monomer (VAM): CH₃COOH + C₂H₄ + O₂ → CH₂=CH-O-CO-CH₃

- Uses: PVA glue, paints, coatings, adhesives

- Production: 7 million tonnes VAM annually

- Acetic anhydride: 2CH₃COOH → (CH₃CO)₂O + H₂O

- Uses: Aspirin synthesis, cellulose acetate (film, fibers)

- Production: 3 million tonnes annually

- Cellulose acetate: For photographic film, cigarette filters, textiles

- Terephthalic acid: For PET plastic production

4. Pharmaceutical and Medical:

- Aspirin production (acetylsalicylic acid synthesis)

- pH adjustment in drug formulations

- Solvent for drug extraction and purification

- Cervical cancer screening (VIA – visual inspection with acetic acid)

- Application: 5% acetic acid highlights precancerous lesions

- Advantage: Low-cost screening in developing countries

5. Textile and Dyeing Industry:

- Mordant for natural dyes (fixes colors to fabric)

- pH control in dyeing baths

- Fabric finishing processes

- Natural fiber treatment

6. Biological Function:

- Metabolic intermediate (acetyl-CoA precursor)

- Vinegar in fermented foods provides acetic acid

- Gut bacteria produce acetate (conjugate base) during fiber fermentation

- Energy source for colonocytes (colon cells)

Global Production:

- Annual production: 15+ million tonnes

- Market value: £10 billion

- Production methods:

- Methanol carbonylation (industrial): CH₃OH + CO → CH₃COOH (90%)

- Fermentation (food-grade): C₂H₅OH + O₂ → CH₃COOH + H₂O (10%)

- Major producers: China (60%), USA (15%), Germany, Japan

Safety:

- Classification: Corrosive (concentrated), irritant (dilute)

- Dilute (<10%): Minimal hazard, food-safe

- Concentrated (>25%): Causes burns with prolonged contact

- Glacial (99%): Corrosive, handle as hazardous chemical

- Exposure limits: TWA 10 ppm

- PPE (concentrated): Goggles, gloves, lab coat

- GRAS status: Generally Recognized As Safe (FDA) for food use

Citric Acid (C₆H₈O₇) – The Food Industry Standard

Formula: C₆H₈O₇ (tricarboxylic acid) IUPAC Name: 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid Ka₁: 7.4 × 10⁻⁴ | pKa₁: 3.13 Ka₂: 1.7 × 10⁻⁵ | pKa₂: 4.76 Ka₃: 4.0 × 10⁻⁷ | pKa₃: 6.40 Molecular Weight: 192.12 g/mol

Molecular Structure: Three carboxylic acid groups (-COOH) One hydroxyl group (-OH) Central carbon chain Chiral molecule (one stereocenter)

Partial Dissociation (Triprotic): C₆H₈O₇ ⇌ H⁺ + C₆H₇O₇⁻ [First dissociation, pKa 3.13] C₆H₇O₇⁻ ⇌ H⁺ + C₆H₆O₇²⁻ [Second dissociation, pKa 4.76] C₆H₆O₇²⁻ ⇌ H⁺ + C₆H₅O₇³⁻ [Third dissociation, pKa 6.40]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: White crystalline powder (anhydrous) or colorless crystals (monohydrate)

- Odor: Odorless

- Taste: Strong sour, tart

- Density: 1.665 g/cm³

- Melting Point: 153°C (anhydrous), 100°C (monohydrate)

- Solubility: Highly soluble in water (1330 g/L at 20°C)

- Non-toxic and biodegradable

Natural Sources:

- Lemons: 5-8% citric acid (highest concentration)

- Limes: 4-6%

- Oranges: 0.9-1.2%

- Grapefruit: 1.2-2.1%

- Berries: 0.5-2%

- Pineapple, kiwi: 0.7-1.5%

- Found in all citrus fruits and many berries

Applications:

1. Food and Beverage Industry (70% of Production):

Soft Drinks and Beverages:

- Usage: 60-70% of all citric acid production

- Concentration: 0.05-0.3% in beverages

- Functions:

- Flavor enhancer (provides tartness)

- pH adjustment (target pH 2.5-3.5)

- Sweetness enhancer (increases perceived sweetness 15%)

- Preservative (inhibits bacterial growth)

- Antioxidant (prevents oxidation and color changes)

- Metal chelator (binds trace metals that cause off-flavors)

- Economics: Cola companies use 400,000+ tonnes annually

Candy and Confectionery:

- Provides sour taste in sour candies

- Concentration: 1-5% for moderate sour, up to 10% for extreme sour

- Sugar crystallization prevention

- Flavor balance in gummies, hard candies

Jams, Jellies, Preserves:

- Pectin activation (requires pH 2.8-3.5 for gelling)

- Gel strength optimization

- Color preservation in fruits

- Extended shelf life

Canned and Frozen Foods:

- pH adjustment for safety (below pH 4.6 prevents botulism)

- Color retention (prevents enzymatic browning)

- Texture maintenance (calcium chelation)

- Flavor enhancement

Dairy Products:

- Ice cream: Emulsification, prevents fat separation

- Cheese: Controls coagulation rate and texture

- Processed cheese: Emulsifier and pH control

Wine and Beer:

- Acidity adjustment

- Flavor balance

- Fermentation control

2. Chelating Agent (20% of Production):

- Binds metal ions (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺)

- Applications:

- Water softening (removes hardness)

- Detergents and cleaning products

- Rust and scale removal

- Metal surface treatment

- Boiler water treatment

- Advantages: Non-toxic, biodegradable (unlike EDTA), food-safe

3. Cosmetics and Personal Care (5%):

- pH adjustment in lotions, creams, shampoos

- Alpha hydroxy acid (AHA) for skin care

- Effervescent bath products

- Hair conditioners (removes mineral buildup)

- Antioxidant in formulations

4. Pharmaceutical Industry (3%):

- Effervescent tablets (reacts with sodium bicarbonate to produce CO₂)

- pH buffering in liquid medications

- Anticoagulant (sodium citrate in blood collection tubes)

- Flavor masking in syrups and chewable tablets

- Preservative in some formulations

5. Industrial and Technical (2%):

- Concrete setting retardant

- Electroplating baths

- Photography chemicals

- Biodegradable cleaning agents

- Oil well acidizing

Production Methods:

Modern: Industrial Fermentation (99% of production)

- Microorganism: Aspergillus niger (black mold)

- Feedstock: Glucose or sucrose (from corn, sugarcane, cassava)

- Process: Submerged fermentation in large bioreactors

- Yield: 100-150 g citric acid per 100 g sugar (70% conversion efficiency)

- Time: 5-10 days per batch

- Purity: 99.5%+ after crystallization

- Advantages: Cost-effective, sustainable, high purity

Historical: Citrus Fruit Extraction (obsolete)

- Process: Calcium citrate precipitation from lemon juice

- Discontinued: 1920s-1950s (replaced by fermentation)

- Reason: Fermentation 10× cheaper, year-round availability

Global Production:

- Annual production: 2.5+ million tonnes

- Market value: £3.5 billion

- Growth rate: 5-6% annually

- Major producers: China (70%), USA (10%), Europe (15%)

- Market drivers: Clean label trends, beverage industry growth, functional foods

Safety:

- Classification: Non-hazardous, food-safe

- GRAS status: Generally Recognized As Safe (FDA, EFSA)

- LD50: >10,000 mg/kg (very low toxicity)

- Dietary intake: 0.5-5 g/day typical consumption

- Health effects: Generally safe; very high doses (>1 g/kg) may cause digestive upset

- Tooth enamel: Erosion risk with prolonged exposure to acidic foods/drinks (pH <4)

- Environmental: Biodegrades rapidly (72-96 hours), non-toxic to aquatic life

Formic Acid (HCOOH) – The Simplest Carboxylic Acid

Formula: HCOOH or CH₂O₂ IUPAC Name: Methanoic acid Ka: 1.8 × 10⁻⁴ pKa: 3.75 Molecular Weight: 46.03 g/mol

Molecular Structure: Simplest carboxylic acid (one carbon atom) Carboxylic acid group (-COOH) Also contains aldehyde character (H-COOH)

Partial Dissociation: HCOOH(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + HCOO⁻(aq) [~4% at 0.1 M]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Colorless fuming liquid

- Odor: Pungent, penetrating

- Density: 1.22 g/cm³

- Boiling Point: 101°C

- Melting Point: 8.4°C

- Miscible with water

- Corrosive to skin (more than acetic acid)

Natural Occurrence:

- Ant venom: 40-60% formic acid (Latin “formica” = ant)

- Bee stings: Traces

- Stinging nettles: Causes burning sensation

- Produced during metabolism of methanol

Applications:

1. Livestock Feed Preservation (Silage – 35% of Use):

- Concentration: 0.3-0.5% of silage weight

- Function: Reduces pH to 4-4.5, inhibits spoilage microorganisms

- Advantages: Improves fermentation, reduces nutrient loss, prevents mold

- Market: 250,000 tonnes formic acid annually for silage

- Economics: Improves feed quality 15-25%, increases animal productivity

2. Leather Tanning (25%):

- Chrome tanning auxiliary

- Reduces pH gradually for controlled penetration

- Improves leather quality and softness

- Environmentally friendlier than traditional methods

3. Textile Dyeing and Finishing (15%):

- Neutralizing agent after bleaching

- pH adjustment for dyeing processes

- Finishing treatments for cotton and wool

4. Rubber Industry (10%):

- Latex coagulation (natural rubber production)

- Replaces sulfuric acid (less corrosive to equipment)

- Produces higher quality rubber

5. Antibacterial Agent (8%):

- Poultry and swine feed additive

- Reduces Salmonella contamination 90%+

- Alternative to antibiotic growth promoters

- EU-approved for animal feed

6. De-icing and Road Maintenance (5%):

- Potassium formate and sodium formate solutions

- Airport runway de-icers (less corrosive than chloride salts)

- Biodegradable alternative to traditional de-icers

- Advantage: Does not damage concrete or aluminum

7. Chemical Synthesis (2%):

- Pharmaceutical intermediates

- Formate ester production

- Reductive amination reactions

Global Production:

- Annual production: 800,000-900,000 tonnes

- Market value: £800 million

- Production methods:

- Methyl formate hydrolysis: HCO-OCH₃ + H₂O → HCOOH + CH₃OH

- CO + water (industrial process)

- Major producers: BASF, Eastman Chemical, Perstorp

Safety:

- Classification: Corrosive, causes burns

- More corrosive than acetic acid (stronger acid)

- Skin contact: Causes painful burns, delayed tissue damage possible

- Inhalation: Respiratory irritation

- Exposure limits: TWA 5 ppm

- PPE: Goggles, acid-resistant gloves, lab coat, fume hood for concentrated solutions

- First aid: Immediate water flush 15+ minutes, medical attention

Carbonic Acid (H₂CO₃) – The Biological Buffer

Formula: H₂CO₃ Ka₁: 4.3 × 10⁻⁷ | pKa₁: 6.37 Ka₂: 4.7 × 10⁻¹¹ | pKa₂: 10.33 Molecular Weight: 62.03 g/mol

Molecular Structure: Central carbon with three oxygens Two O-H bonds (acidic hydrogens) One C=O double bond

Formation: CO₂(aq) + H₂O(l) ⇌ H₂CO₃(aq) [Equilibrium favors left]

Partial Dissociation: H₂CO₃(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + HCO₃⁻(aq) [First dissociation, pKa 6.37] HCO₃⁻(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + CO₃²⁻(aq) [Second dissociation, pKa 10.33]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Exists only in aqueous solution

- Stability: Cannot be isolated (decomposes to CO₂ + H₂O)

- Equilibrium: Most “carbonic acid” is actually dissolved CO₂

- Concentration: Very low in solution (most CO₂ remains as CO₂(aq))

Biological Importance:

1. Blood pH Regulation (Primary Buffer System in Humans):

The Bicarbonate Buffer System: CO₂ + H₂O ⇌ H₂CO₃ ⇌ H⁺ + HCO₃⁻

Normal Blood Values:

- pH: 7.35-7.45 (tightly controlled)

- pCO₂: 35-45 mmHg

- HCO₃⁻: 22-26 mEq/L

- Ratio: [HCO₃⁻]/[H₂CO₃] = 20:1 (maintains pH 7.4)

Buffer Mechanism:

Excess Acid (H⁺): H⁺ + HCO₃⁻ → H₂CO₃ → CO₂ + H₂O → Exhaled

- Bicarbonate neutralizes acid

- CO₂ removed by lungs

- pH returns to normal

Excess Base (OH⁻): OH⁻ + H₂CO₃ → HCO₃⁻ + H₂O

- Carbonic acid neutralizes base

- Kidneys excrete excess bicarbonate

- pH returns to normal

Control Systems:

- Respiratory: Adjusts CO₂ levels (minutes)

- Renal: Adjusts HCO₃⁻ levels (hours to days)

Clinical Significance:

- Acidosis: pH <7.35 (excess H⁺ or low HCO₃⁻)

- Respiratory acidosis: High pCO₂ (hypoventilation)

- Metabolic acidosis: Low HCO₃⁻ (diabetes, kidney disease)

- Alkalosis: pH >7.45 (loss of H⁺ or excess HCO₃⁻)

- Respiratory alkalosis: Low pCO₂ (hyperventilation)

- Metabolic alkalosis: High HCO₃⁻ (vomiting, diuretics)

Capacity:

- Handles 15,000-20,000 mmol CO₂ daily from metabolism

- 70% of blood’s buffering capacity

- Essential for life (pH deviations >0.2 units can be fatal)

2. Carbonated Beverages:

- CO₂ dissolved under pressure forms carbonic acid

- Typical pH: 3.5-4.0 (from CO₂ + other acids)

- “Fizz”: CO₂ released when pressure drops

- Carbonic acid provides mild acidity and “bite”

- Chemistry: CO₂(aq) ⇌ H₂CO₃ ⇌ H⁺ + HCO₃⁻

3. Ocean Chemistry:

- Dissolved CO₂ in seawater forms carbonic acid

- Marine pH regulation

- Calcium carbonate shell formation: Ca²⁺ + CO₃²⁻ → CaCO₃

- Ocean acidification: Increased atmospheric CO₂ → More H₂CO₃ → Lower pH

Climate Change Impact (2024 Data):

- Pre-industrial ocean pH: 8.2

- Current ocean pH: 8.1 (26% increase in acidity)

- Projected 2100 pH: 7.8 (150% increase if emissions continue)

- Consequences: Coral bleaching, shell dissolution, ecosystem disruption

4. Geological Processes:

- Limestone caves formation: H₂CO₃ + CaCO₃ → Ca(HCO₃)₂ (soluble)

- Stalactites and stalagmites: Reverse reaction deposits CaCO₃

- Rock weathering: Carbonic acid slowly dissolves minerals

- Carbon cycle: Weathering sequesters atmospheric CO₂ over geological time

Safety:

Environmental: Part of natural carbon cycle

Classification: Non-hazardous (very weak acid, low concentration)

Natural: Present in all carbonated water and bodily fluids

Toxicity: None (essential for life)

Phosphoric Acid (H₃PO₄) – The Beverage and Fertilizer Acid

Formula: H₃PO₄ Ka₁: 7.5 × 10⁻³ | pKa₁: 2.12 Ka₂: 6.2 × 10⁻⁸ | pKa₂: 7.21 Ka₃: 4.8 × 10⁻¹³ | pKa₃: 12.32 Molecular Weight: 97.99 g/mol

Classification Note: Although Ka₁ suggests moderate strength, phosphoric acid is classified as weak because it doesn’t completely dissociate. Second and third dissociations are definitely weak.

Molecular Structure: Central phosphorus atom Four oxygen atoms (tetrahedral geometry) Three O-H bonds (three acidic hydrogens = triprotic)

Partial Dissociation (Triprotic): H₃PO₄ ⇌ H⁺ + H₂PO₄⁻ [First dissociation, pKa 2.12] H₂PO₄⁻ ⇌ H⁺ + HPO₄²⁻ [Second dissociation, pKa 7.21] HPO₄²⁻ ⇌ H⁺ + PO₄³⁻ [Third dissociation, pKa 12.32]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Clear, colorless, odorless liquid (85% solution)

- Density: 1.685 g/cm³ (85% solution)

- Melting Point: 42.4°C (pure)

- Viscosity: Syrupy consistency

- Non-volatile

- Hygroscopic (absorbs moisture)

Applications:

1. Soft Drinks and Beverages (Food-Grade, 5%):

- Primary use: Cola-type beverages

- Concentration: 0.05-0.08% in finished product

- Functions:

- Acidulant: Provides tart, tangy flavor

- pH control: Maintains pH 2.5-3.0

- Flavor enhancer: Complements vanilla and caramel notes

- Sweetness enhancer

- Prevents microbial growth

- Usage: 95% of colas use phosphoric acid (not citric acid)

- Market: 200,000 tonnes food-grade H₃PO₄ annually

- Iconic taste: Gives cola its characteristic sharp taste (vs citric acid’s fruity taste)

Health Considerations:

- Tooth enamel erosion: Acidic pH (2.5-3.0) can soften enamel with frequent exposure

- Bone health controversy: Some studies suggest high phosphate intake may affect calcium metabolism (inconclusive)

- Kidney stones: High phosphate may increase risk in susceptible individuals

- Safe consumption: FDA and EFSA approve use in beverages (GRAS status)

2. Fertilizer Production (Industrial-Grade, 90%):

- Largest use of phosphoric acid globally

- Phosphate fertilizers: DAP (diammonium phosphate), MAP (monoammonium phosphate), TSP (triple superphosphate)

- Production: Phosphate rock + H₂SO₄ → H₃PO₄ + CaSO₄

- Then: H₃PO₄ + NH₃ → NH₄H₂PO₄ (MAP) or (NH₄)₂HPO₄ (DAP)

- Scale: 40+ million tonnes H₃PO₄ for fertilizers annually

- Impact: Essential for global food production (phosphorus is plant macronutrient)

- Economic value: £35 billion fertilizer market

3. Rust Removal and Metal Treatment (3%):

- Converts rust to stable black iron phosphate coating

- Mechanism: Fe₂O₃ + 2H₃PO₄ → 2FePO₄ + 3H₂O

- Applications: Rust converters, metal primers, phosphate coatings

- Advantages: Rust removal + protective coating in one step

- Products: Naval Jelly, Rust-Oleum rust converter

4. Detergents and Cleaning Products (1.5%):

- Water softening (chelates calcium and magnesium)

- pH buffering

- Cleaning enhancer

- Note: Phosphate use declining due to environmental concerns (eutrophication)

5. Pharmaceutical and Medical (0.3%):

- pH buffering in IV solutions

- Pharmaceutical formulations

- Laxative preparations (sodium phosphate enemas)

- Dental etching (orthodontics)

6. Industrial Applications (0.2%):

- Electropolishing of metals

- Rust-proofing coatings (phosphate conversion coatings)

- Refractory materials

- Flame retardants

Production Methods:

Wet Process (90% of production): Ca₃(PO₄)₂ + 3H₂SO₄ → 2H₃PO₄ + 3CaSO₄

- Raw material: Phosphate rock (mainly Florida, Morocco, China)

- Product purity: 54% P₂O₅ (technical grade)

- Use: Fertilizers, industrial applications

Thermal Process (10% of production): Ca₃(PO₄)₂ + 3SiO₂ + 5C → 3CaSiO₃ + 5CO + 2P 4P + 5O₂ → 2P₂O₅ P₂O₅ + 3H₂O → 2H₃PO₄

- Product purity: >99% (food-grade, pharmaceutical-grade)

- Use: Food, beverages, pharmaceuticals

- Cost: 3-5× more expensive than wet process

Global Production:

- Annual production: 45+ million tonnes (mostly for fertilizers)

- Food-grade production: ~2 million tonnes

- Market value: £40 billion (total), £2 billion (food-grade)

- Major producers: China (50%), Morocco (15%), USA (10%)

Safety:

- Classification: Corrosive (concentrated), irritant (dilute)

- Food-grade: GRAS status, safe for consumption in regulated amounts

- Concentrated (>85%): Causes skin and eye burns

- Dilute (<10%): Mild irritant

- Exposure limits: TWA 1 mg/m³

- PPE (concentrated): Goggles, gloves, lab coat

- Environmental: Eutrophication concern (algal blooms in water bodies)

Lactic Acid (C₃H₆O₃) – The Fermentation and Bioplastic Acid

Formula: C₃H₆O₃ or CH₃CHOHCOOH IUPAC Name: 2-hydroxypropanoic acid Ka: 1.4 × 10⁻⁴ pKa: 3.86 Molecular Weight: 90.08 g/mol

Molecular Structure: Carboxylic acid group (-COOH) Hydroxyl group (-OH) on carbon-2 Methyl group (CH₃) Chiral molecule: Exists as D(-) and L(+) enantiomers

Partial Dissociation: CH₃CHOHCOOH(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + CH₃CHOHCOO⁻(aq) [~3.7% at 0.1 M]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Clear, colorless to slightly yellow syrup

- Odor: Mild, slightly sour

- Taste: Sour with creamy notes

- Density: 1.21 g/cm³

- Melting Point: 53°C

- Hygroscopic

- Miscible with water

Biological Sources:

1. Muscle Metabolism:

- Produced during anaerobic glycolysis

- Glucose → 2 Pyruvate → 2 Lactate + 2 ATP

- Normal blood lactate: 0.5-2.2 mmol/L at rest

- Exercise: Can rise to 15-20 mmol/L during intense activity

- Function: Energy substrate (not just “waste product”)

- Lactate paradox: Used as fuel by heart, brain, and resting muscles

2. Fermented Foods:

- Yogurt: 0.7-1.2% lactic acid (characteristic tang)

- Sauerkraut: 1.5-2.0%

- Sourdough bread: 0.3-0.7%

- Kimchi: 0.8-1.5%

- Pickles (lacto-fermented): 1.0-1.5%

- Cheese: 0.5-2.0%

- Produced by Lactobacillus bacteria

Applications:

1. Food Industry (40% of production):

Meat Preservation:

- Surface treatment: 2-5% lactic acid spray

- Pathogen reduction: 99.9% reduction in E. coli, Salmonella, Listeria

- Shelf life: 50-100% extension

- FDA approved: 1994 for beef, pork, poultry

- Advantages: No off-flavors, no color change, natural

pH Control and Acidulant:

- Milder sourness than citric or acetic acid

- Clean, creamy acidic taste

- Masks bitter flavors in foods

- Natural preservation

Beverage Applications:

- Sports drinks: Sodium lactate for electrolytes + energy source

- Probiotic beverages

- pH adjustment in kombuchas

- Fermented drink base

2. Biodegradable Plastics – PLA (30% of production):

Polylactic Acid (PLA) Production: Lactic acid → Lactide (cyclic dimer) → Polymerization → PLA polymer

Properties:

- Biodegradable: Degrades in 6-12 months in composting conditions

- Compostable: Industrial composting facilities (55-60°C)

- Transparent like PET plastic

- Moderate strength and stiffness

- Heat-sensitive: Deforms above 60°C

Applications:

- Food packaging: Cups, containers, films, trays

- 3D printing filament: Popular for desktop 3D printers

- Medical: Absorbable sutures, implants, drug delivery

- Textiles: Fibers for clothing (moisture-wicking)

- Agriculture: Biodegradable mulch films

Market Growth:

- 2020: 200,000 tonnes PLA production

- 2024: 500,000 tonnes

- Projected 2030: 2+ million tonnes

- Growth rate: 18% annually

- Market value: £2 billion (2024), projected £8 billion (2030)

- Driver: Plastic pollution concerns, sustainability

3. Cosmetics and Personal Care (15%):

Alpha Hydroxy Acid (AHA) Applications:

- Chemical peels: 20-70% lactic acid

- Exfoliation: Removes dead skin cells

- Anti-aging: Stimulates collagen production, reduces wrinkles

- Moisturizing: Increases skin hydration

- Brightening: Reduces hyperpigmentation

- Acne treatment: Unclogs pores

Concentrations:

- Daily use products: 5-10% (pH 3.5-4.0)

- Professional peels: 30-70% (pH 2.0-3.0)

- Medical treatments: Up to 88%

Advantages over other AHAs:

- Larger molecule: Gentler, less irritation

- Naturally present in skin (NMF – natural moisturizing factor)

- Better for sensitive skin

- Hydrating properties

Market:

- AHA cosmetics: £200+ million market

- Growth: 7% annually

- Popular in Korean beauty (K-beauty) products

4. Pharmaceutical Industry (10%):

- Ringer’s lactate solution: IV fluid for resuscitation, surgery

- Calcium lactate: Calcium supplement

- Iron lactate: Iron supplement (better absorption than iron sulfate)

- pH adjustment in formulations

- Drug delivery systems

5. Industrial Applications (5%):

- Leather tanning

- Textile dyeing and finishing

- Descaling and cleaning agents

- Biodegradable solvents

Production Methods:

Fermentation (90% of production):

- Microorganism: Lactobacillus species

- Feedstock: Glucose, sucrose, molasses, starch

- Process: Batch or continuous fermentation

- Yield: 90-95% conversion efficiency

- Purity: 88-92% after purification

- Enantiomer: Depends on bacterial strain (L-lactate or D-lactate)

Chemical Synthesis (10%, declining):

- Lactonitrile hydrolysis

- Produces racemic mixture (50:50 L/D)

- Disadvantage: Less pure, not “natural” for food use

Global Production:

- Annual production: 1.2+ million tonnes

- Food-grade: 500,000 tonnes

- PLA-grade: 600,000 tonnes (growing rapidly)

- Market value: £2 billion

- Major producers: Corbion (Netherlands), Henan Jindan (China), Galactic (Belgium)

Safety:

Environmental: Biodegradable, non-toxic

Classification: Non-hazardous, food-safe

GRAS status: Generally Recognized As Safe (FDA)

LD50: >2,000 mg/kg (low toxicity)

Skin: High concentrations irritate (cosmetic peels)

Dietary: Natural component of many foods

Oxalic Acid (C₂H₂O₄) – The Strongest Weak Acid

Formula: C₂H₂O₄ or HOOC-COOH IUPAC Name: Ethanedioic acid Ka₁: 5.9 × 10⁻² | pKa₁: 1.23 Ka₂: 6.4 × 10⁻⁵ | pKa₂: 4.19 Molecular Weight: 90.03 g/mol

Molecular Structure: Two carboxylic acid groups directly bonded Simplest dicarboxylic acid Planar molecule

Partial Dissociation: H₂C₂O₄ ⇌ H⁺ + HC₂O₄⁻ [~24% at 0.1 M, pKa 1.23] HC₂O₄⁻ ⇌ H⁺ + C₂O₄²⁻ [Second dissociation, pKa 4.19]

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: White crystalline solid (dihydrate common)

- Odor: Odorless

- Taste: Sour

- Density: 1.90 g/cm³

- Melting Point: 189°C (anhydrous decomposes)

- Solubility: 100 g/L in water (25°C)

- Toxic: More toxic than other common weak acids

Natural Occurrence:

- Rhubarb leaves: 0.5% oxalic acid (toxic—don’t eat leaves!)

- Spinach: 0.3-1.0% (high concentration)

- Chard, beet greens: 0.3-0.6%

- Cocoa and chocolate: 0.1-0.5%

- Tea: 0.3-2.0%

- Nuts: 0.1-0.5%

- Many other plants: Defense compound against herbivores

Applications:

1. Rust and Stain Removal (40%):

- Removes iron stains and rust: Fe₂O₃ + 6H₂C₂O₄ → 2Fe(C₂O₄)₃⁴⁻ + 3H₂O + 6H⁺

- Bar Keeper’s Friend: Contains oxalic acid

- Wood deck cleaning: Removes iron stains from tannins

- Automobile radiator cleaning

- Concentration: 5-10% solutions

- Advantages: Effective, inexpensive, relatively safe when handled properly

2. Textile and Wood Industries (25%):

- Bleaching agent for wood and textiles

- Removes mineral stains

- Leather tanning

- Fabric rust stain removal

3. Metal Polishing and Cleaning (20%):

- Stainless steel cleaning

- Aluminum brightening

- Brass and copper polishing

- Removes oxidation and discoloration

4. Analytical Chemistry (10%):

- Primary standard for permanganate standardization

- Titration reactions: 5H₂C₂O₄ + 2MnO₄⁻ + 6H⁺ → 2Mn²⁺ + 10CO₂ + 8H₂O

- Gravimetric analysis

- Calcium determination

5. Pharmaceutical Intermediates (3%):

- Synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds

- Chemical intermediate

- Rare earth metal extraction

6. Industrial Processes (2%):

- Rare earth metal purification

- Uranium processing

- Photography chemicals (historical)

Health Considerations:

Kidney Stones:

- Calcium oxalate: 80% of kidney stones

- Formation: Ca²⁺ + C₂O₄²⁻ → CaC₂O₄ (insoluble crystals)

- High dietary oxalate increases risk in susceptible individuals

- Recommendations: Limit high-oxalate foods if prone to stones

Dietary Management:

- High-oxalate foods: Spinach (750 mg/100g), rhubarb (500 mg/100g), beets (330 mg/100g)

- Cooking reduces oxalate 30-90% (leaches into water)

- Calcium intake: Adequate calcium binds oxalate in gut, reducing absorption

- Hydration: Dilutes urine, reduces crystallization

Toxicity:

- Acute toxicity: 5-15 g can be fatal

- Mechanism: Precipitates calcium (hypocalcemia), kidney damage, cardiac effects

- Rhubarb leaves: Contain ~0.5% oxalic acid—don’t consume!

- Treatment: Calcium supplementation, supportive care

Global Production:

- Annual production: 120,000 tonnes

- Market value: £150 million

- Production method: Sodium formate oxidation, or sawdust/carbohydrate oxidation

- Major producers: India, China

Safety:

- Classification: Harmful, irritant, toxic in high doses

- Skin contact: Irritation, burns with concentrated solutions

- Ingestion: Toxic—medical attention required

- LD50: 375 mg/kg (rat, oral) – moderately toxic

- Exposure limits: TWA 1 mg/m³

- PPE: Gloves, goggles, avoid dust inhalation

- First aid: Water flush, medical attention for ingestion

- Antidote: Calcium gluconate for exposure

Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) – The Dangerous Weak Acid

Formula: HF Ka: 3.5 × 10⁻⁴ pKa: 3.17 Molecular Weight: 20.01 g/mol

CRITICAL WARNING: Despite being classified as a WEAK acid by Ka value, HF is EXTREMELY DANGEROUS and requires specialized training. Never confuse “weak acid” (ionization behavior) with “safe.”

Molecular Structure: Simple diatomic molecule: H-F bond Shortest and strongest H-X bond Extensive hydrogen bonding in liquid phase

Partial Dissociation: HF(aq) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + F⁻(aq) [~7.5% at 0.1 M]

Why HF is Weak (Chemically):

- Strong H-F bond (565 kJ/mol)

- Extensive hydrogen bonding stabilizes molecular form

- Low Ka value (3.5 × 10⁻⁴) = weak acid by definition

- Only partially dissociates

Why HF is Extremely Dangerous (Biologically):

Unique Hazards:

- Penetrates tissue deeply without immediate pain

- Delayed pain (1-8 hours after exposure)

- Interferes with nerve function (prevents pain sensation initially)

- Attacks bones (F⁻ binds calcium, causes hypocalcemia)

- Systemic toxicity from small skin exposures (>2% body surface area can be fatal)

- Heart arrhythmias from calcium binding

- Destroys glass (unique among common acids)

Mechanism of Toxicity:

- Undissociated HF penetrates skin/tissue rapidly

- Dissociates inside tissue: HF → H⁺ + F⁻

- F⁻ ions bind Ca²⁺: Ca²⁺ + 2F⁻ → CaF₂ (insoluble)

- Hypocalcemia causes cardiac arrest, neuromuscular effects

- Destruction continues for hours without treatment

Physical Properties:

- Appearance: Colorless liquid or gas

- Odor: Pungent, sharp

- Boiling Point: 19.5°C (liquid at room temp if concentrated)

- Density: 0.99 g/cm³ (70% solution)

- Fumes readily

- Etches glass (stored in plastic or wax-coated bottles)

Unique Property – Dissolves Glass: SiO₂ + 6HF → H₂SiF₆ + 2H₂O

- Only common acid that attacks silica/glass

- Requires plastic (HDPE, PTFE) containers

- Used for glass etching and frosting

Applications:

1. Glass Etching and Frosting (20%):

- Decorative glass patterns

- Frosted glass surfaces

- Glassware markings

- Mirror silvering removal

- Art glass production

2. Semiconductor Manufacturing (40%):

- Silicon wafer etching

- Oxide removal

- Microelectronics fabrication

- Critical for £500+ billion semiconductor industry

- Ultrapure HF required (ppb impurities)

3. Fluoropolymer Production (15%):

- Teflon (PTFE) manufacturing

- Fluoroelastomers

- Fluoroplastics

- Non-stick coatings

4. Petroleum Refining (10%):

- Alkylation catalyst (produces high-octane gasoline)

- Removes sulfur impurities

- Fluorine chemistry applications

5. Uranium Processing (5%):

- Nuclear fuel cycle

- UO₂ + 4HF → UF₄ + 2H₂O

- Uranium enrichment (converts to UF₆)

6. Stainless Steel Pickling (5%):

- Removes oxide layers

- Mixed with nitric acid

- Superior to other acids for stainless steel

7. Analytical Chemistry (3%):

- Dissolves silicate minerals for analysis

- Sample preparation

- Specialized applications

8. Other (2%):

- Metal surface treatment

- Chemical synthesis

- Fluorine compound production

Global Production:

- Annual production: ~1 million tonnes

- Market value: £2 billion

- Production: CaF₂ (fluorite) + H₂SO₄ → 2HF + CaSO₄

- Major producers: China, Mexico, USA

Specialized Safety Protocols:

Before ANY Work with HF:

- Specialized training mandatory (4-8 hours minimum)

- Medical clearance required

- Emergency procedures practiced and posted

- Calcium gluconate gel immediately available (antidote)

- Dedicated HF fume hood with continuous monitoring

- Buddy system (never work alone)

- Emergency medical arrangements with hospitals experienced in HF burns

PPE Requirements:

- Face shield (in addition to goggles)

- Double gloves: Neoprene or butyl rubber (HF-resistant, NOT nitrile or latex)

- Full chemical suit or thick rubber apron

- Closed-toe shoes with covers

- No exposed skin anywhere

Emergency Equipment:

- Calcium gluconate gel tubes (multiple locations)

- Emergency shower within 5 seconds

- Eyewash station within 5 seconds

- Emergency phone with posted numbers

- HF spill kit

- Emergency medical protocol posted

First Aid (Immediate):

- Remove from exposure immediately

- Remove contaminated clothing under water

- Flush with water continuously (20+ minutes minimum)

- Apply calcium gluconate gel immediately and massively

- Massage into affected area

- Reapply every 15 minutes

- Call emergency medical services immediately

- Continue treatment en route to hospital

- Monitor cardiac rhythm (ECG)

- Hospital treatment: IV calcium gluconate, cardiac monitoring, potential surgical debridement

Exposure Effects by Concentration:

<20% HF:

- Delayed pain (1-8 hours)

- Tissue destruction continues without pain

- Requires calcium gluconate treatment

20-50% HF:

- Pain in 1-2 hours

- Severe tissue damage

- High systemic toxicity risk

>50% HF:

- Immediate pain

- Rapid tissue destruction

- Extreme systemic toxicity risk

- Potential fatality from small exposures

Lethal Dose:

- Skin exposure >2% body surface area (70 kg person: ~40 cm²)

- Can be fatal with treatment delay

Storage Requirements:

- Polyethylene (HDPE) or PTFE containers only

- Secondary containment mandatory

- Separated from all other chemicals

- Cool, well-ventilated area

- Limited quantities (only what needed)

- Inventory tracking

- Restricted access

Regulatory:

Hazmat transportation rules

OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1000: PEL = 3 ppm (TWA)

Highly regulated chemical

Reporting requirements for spills

Comparison Table: Common Weak Acids

| Weak Acid | Formula | pKa | % Ionization (0.1 M) | Primary Use | Global Production | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxalic | C₂H₂O₄ | 1.23 | ~24% | Rust removal | 120,000 t/yr | Toxic |

| Phosphoric | H₃PO₄ | 2.12 | ~12% | Fertilizers/Beverages | 45 M t/yr | Irritant |

| Citric | C₆H₈O₇ | 3.13 | ~8% | Food/Beverages | 2.5 M t/yr | Non-hazardous |

| Hydrofluoric | HF | 3.17 | ~7.5% | Semiconductors | 1 M t/yr | EXTREME DANGER |

| Formic | HCOOH | 3.75 | ~4.2% | Livestock feed | 850,000 t/yr | Corrosive |

| Lactic | C₃H₆O₃ | 3.86 | ~3.7% | Food/PLA plastics | 1.2 M t/yr | Non-hazardous |

| Acetic | CH₃COOH | 4.76 | ~1.3% | Food/Chemicals | 15 M t/yr | Irritant |

| Carbonic | H₂CO₃ | 6.37 | ~0.006% | Blood buffer | Natural only | Non-hazardous |

Key Differences: Strong vs Weak Acids

Understanding how strong and weak acids differ across multiple dimensions is essential for predicting behavior, ensuring safety, and selecting the right acid for any application.

1. Ionization Behavior – The Fundamental Distinction

Strong Acids:

- Complete dissociation (100% ionization)

- Irreversible one-way reaction

- All molecules convert to ions

- No equilibrium exists

- No reverse reaction

- Represented with single arrow (→)

- Forward reaction rate >> reverse reaction rate

- Ka >> 1 (often >10³)

Example: 1.0 M HCl

- Before: 1.0 mole HCl molecules

- After: 0 mole HCl, 1.0 mole H⁺, 1.0 mole Cl⁻

- Ionization: 100%

Weak Acids:

- Partial dissociation (1-10% typical ionization)

- Reversible equilibrium reaction

- Majority remains molecular (90-99%)

- Dynamic equilibrium established

- Forward and reverse reactions occur simultaneously

- Represented with double arrow (⇌)

- Forward rate ≈ reverse rate at equilibrium

- Ka << 1 (typically 10⁻² to 10⁻¹⁵)

Example: 1.0 M CH₃COOH

- Before: 1.0 mole CH₃COOH molecules

- After: 0.996 mole CH₃COOH, 0.004 mole H⁺, 0.004 mole CH₃COO⁻

- Ionization: 0.4%

Quantitative Comparison at 0.1 M:

- Strong acid: 0.1 M H⁺ ions (100%)

- Weak acid: 0.001-0.01 M H⁺ ions (1-10%)

- Difference: 10-100 fold

2. pH Values at Equal Concentrations

Strong Acids:

- Very low pH values (often pH <1 at 1 M)

- pH directly calculable from concentration: pH = -log[acid]

- Linear relationship with dilution

- Predictable pH changes

- No buffering capacity

- pH changes dramatically with small additions

Weak Acids:

- Moderate pH values (typically pH 2-6 depending on Ka)

- pH requires Ka and equilibrium calculations

- Non-linear relationship with dilution

- Complex pH predictions

- Excellent buffering capacity (especially near pKa)

- pH resists changes

pH Comparison Table:

| Concentration (M) | HCl (Strong) pH | Acetic Acid (Weak, pKa = 4.76) pH | Difference | [H⁺] Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 units | 250× |

| 0.1 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 1.9 units | 80× |

| 0.01 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 1.4 units | 25× |

| 0.001 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 0.9 units | 8× |

Key Insight: Even at identical concentrations, strong acids are 8-250× more acidic than typical weak acids.

3. Reaction Kinetics and Speed

Strong Acids:

- Extremely fast reactions (seconds to minutes)

- High [H⁺] available immediately

- Vigorous, often violent reactions with metals/bases

- Rapid, exothermic heat generation

- Complete reactions quickly

- Rate-limited by diffusion, not ionization

- Observable: Vigorous bubbling, heat, rapid color changes

Weak Acids:

- Slower, controlled reactions (minutes to hours)

- Limited [H⁺] initially available

- Gentle, gradual reactions

- Moderate heat generation

- May take extended time to complete

- Rate-limited by ionization equilibrium

- Observable: Gentle bubbling, minimal heating, slow changes

Zinc Metal Reaction Comparison:

With 0.1 M HCl (Strong):

- Reaction start: Immediate (within 1 second)

- Bubbling: Vigorous, continuous stream

- H₂ gas production: ~15-20 mL/min

- Temperature increase: +15-25°C

- Zinc dissolution: Complete in 5-10 minutes

- Observation: Violent effervescence

With 0.1 M CH₃COOH (Weak):

- Reaction start: Delayed (15-30 seconds)

- Bubbling: Gentle, occasional bubbles

- H₂ gas production: ~0.5-1 mL/min

- Temperature increase: +2-5°C

- Zinc dissolution: 2-4 hours

- Observation: Slow, controlled reaction

Rate Difference: Strong acids react 20-50× faster than weak acids at equivalent concentrations.

Calcium Carbonate (Marble) Reaction:

With HCl: CaCO₃ + 2HCl → CaCl₂ + H₂O + CO₂

- Immediate vigorous fizzing

- Marble dissolves in minutes

- Rapid CO₂ evolution

With CH₃COOH: CaCO₃ + 2CH₃COOH → Ca(CH₃COO)₂ + H₂O + CO₂

- Slow, gentle fizzing

- Marble takes hours to dissolve

- Gradual CO₂ evolution

4. Electrical Conductivity

Strong Acids:

- Excellent electrical conductors

- High ion concentration enables current flow

- Used in batteries and electrochemical cells

- Conductivity directly proportional to concentration

- Typical conductivity: 100-400 mS/cm at 0.1 M

- Essential for electrical applications

Weak Acids:

- Poor to moderate electrical conductors

- Low ion concentration limits current

- Generally unsuitable for battery applications

- Conductivity not proportional to concentration

- Typical conductivity: 1-5 mS/cm at 0.1 M

- Inadequate for most electrical uses

Conductivity Comparison at 0.1 M:

- 0.1 M HCl: ~390 mS/cm

- 0.1 M CH₃COOH: ~5 mS/cm

- Ratio: ~78:1 (HCl conducts 78× better)

Practical Demonstration: Simple conductivity test with light bulb circuit:

- 0.1 M HCl: Bulb shines brightly

- 0.1 M acetic acid: Bulb barely glows or doesn’t light

- Pure water: No light (essentially non-conductive)

Why This Matters:

- Car batteries use H₂SO₄ (strong acid) for high conductivity

- Weak acids cannot provide sufficient ion concentration for electrical applications

- Conductivity measurement helps identify strong vs weak acids

5. Buffering Capacity and Equilibrium Behavior

Strong Acids:

- NO buffering capacity

- pH changes dramatically with dilution

- Cannot resist pH changes

- Poor pH stability

- No equilibrium to shift

- pH changes proportionally with concentration changes

Weak Acids:

- Excellent buffering capacity (especially at pH = pKa ± 1)

- pH resists changes with dilution

- Maintains stable pH with small additions of acid/base

- Essential for biological pH regulation

- Equilibrium shifts to accommodate changes

- pH changes less than proportionally

Dilution Effect Comparison:

Starting with 1.0 M acid, dilute to 0.1 M (10-fold dilution):

HCl (Strong):

- Initial pH: 0.0

- Final pH: 1.0

- Change: Exactly +1.0 unit (no buffering)

Acetic Acid (Weak):

- Initial pH: 2.4

- Final pH: 2.9

- Change: Only +0.5 units (buffered)

Why Different? As weak acid dilutes, equilibrium shifts right (Le Chatelier’s principle): CH₃COOH ⇌ H⁺ + CH₃COO⁻

Lower concentration → More dissociation → Partially compensates for dilution → pH increases less

Biological Significance:

Blood pH regulation (7.35-7.45) uses carbonic acid/bicarbonate buffer: CO₂ + H₂O ⇌ H₂CO₃ ⇌ H⁺ + HCO₃⁻

When acid enters blood: H⁺ + HCO₃⁻ → H₂CO₃ → CO₂ + H₂O (exhaled) When base enters blood: OH⁻ + H₂CO₃ → HCO₃⁻ + H₂O

This weak acid buffer maintains stable pH despite:

- 15,000-20,000 mmol CO₂ produced daily from metabolism

- Dietary acids and bases

- Exercise-induced lactate production

Critical Point: Strong acids CANNOT provide this buffering. Blood pH would fluctuate wildly, causing death. Life depends on weak acid buffers.

Buffer Capacity Statistics:

- 95% of biological pH regulation uses weak acid/base equilibria

- Deviation of blood pH by >0.2 units can be fatal

- pH 7.0 (acidosis) or pH 7.8 (alkalosis): Medical emergency

6. Conjugate Base Strength

Strong Acids:

- Extremely weak conjugate bases

- Conjugate base essentially non-basic

- No tendency to accept protons

- Stable as ions in solution

- Do not reform the acid

Examples:

- HCl → Cl⁻ (chloride ion: pKb ≈ 20, essentially neutral)

- HNO₃ → NO₃⁻ (nitrate ion: pKb ≈ 15, essentially neutral)

- H₂SO₄ → HSO₄⁻ (bisulfate ion: pKb ≈ 12, very weak base)

Weak Acids:

- Moderately strong to strong conjugate bases

- Conjugate base readily accepts protons

- Significant tendency to reform the acid

- Creates equilibrium with acid form

- Active participants in buffering

Examples:

- CH₃COOH ⇌ CH₃COO⁻ (acetate ion: pKb = 9.24, weak base)

- H₂CO₃ ⇌ HCO₃⁻ (bicarbonate ion: pKb = 7.63, moderate base)

- HPO₄²⁻ ⇌ PO₄³⁻ (phosphate ion: pKb = 1.68, strong base)

The Inverse Relationship Rule:

pKa + pKb = 14 (at 25°C)

- Stronger acid (lower pKa) → Weaker conjugate base (higher pKb)

- Weaker acid (higher pKa) → Stronger conjugate base (lower pKb)

Practical Example:

Strong Acid: HCl: pKa = -7 → Cl⁻: pKb = 21 (no basicity)

Weak Acid: CH₃COOH: pKa = 4.76 → CH₃COO⁻: pKb = 9.24 (weak base)

When sodium acetate (CH₃COONa) dissolves in water: CH₃COO⁻ + H₂O ⇌ CH₃COOH + OH⁻

Solution becomes slightly basic (pH ~9)!

When sodium chloride (NaCl) dissolves: Cl⁻ + H₂O → No reaction

Solution stays neutral (pH 7).

7. Safety and Handling Requirements

Strong Acids:

- Extremely hazardous

- Cause severe burns within seconds

- Tissue destruction immediate

- Produce dangerous vapors (respiratory hazards)

- Require extensive protective equipment

- Specialized storage (corrosion-resistant cabinets, secondary containment)

- High emergency response costs

- Dedicated acid spill kits mandatory

- Emergency eyewash/shower within 10 seconds required

- Extensive training necessary (8-16 hours minimum)

Safety Statistics:

- 15× more workplace injuries than weak acids

- 78% of acid-related accidents involve strong acids

- Only 30% of acid usage by volume

- Average medical cost: £25,000 per injury

- Lost work time: 14 days average

Weak Acids:

- Generally safer to handle

- Cause burns with prolonged exposure (minutes to hours)

- Time available for emergency response

- Lower vapor hazards

- Standard protective equipment usually sufficient

- Simpler storage (standard chemical cabinets)

- Lower emergency costs

- Basic training sufficient (2-4 hours)

- Manageable risk profile

Safety Statistics:

- 22% of acid-related accidents

- 70% of acid usage by volume

- Average medical cost: £1,500 per exposure

- Lost work time: 2 days average

EXCEPTION: Hydrofluoric Acid Despite being weak (Ka = 3.5 × 10⁻⁴), HF is EXTREMELY DANGEROUS:

- Penetrates tissue deeply

- Delayed pain (no immediate warning)

- Attacks bones (binds calcium)

- Can be fatal from <2% body surface area exposure

- Requires specialized HF training and protocols

PPE Comparison:

Strong Acids:

- Chemical splash goggles + full face shield

- Heavy-duty acid-resistant gloves (neoprene, butyl rubber)

- Full-length lab coat or chemical suit

- Closed-toe shoes with chemical-resistant covers

- Respirator if inadequate ventilation

- No exposed skin anywhere

Weak Acids (Dilute):

- Safety glasses with side shields

- Nitrile or latex gloves

- Standard lab coat

- Closed-toe shoes

- Normal laboratory ventilation

Weak Acids (Concentrated):

- Chemical splash goggles

- Acid-resistant gloves

- Lab coat or apron

- Fume hood recommended

8. Economic and Practical Considerations

Strong Acids:

- Higher total operational costs (5-10× more expensive)

- Specialized equipment required (corrosion-resistant materials)

- Extensive training necessary (£500-2,000 per person)

- Complex regulatory compliance (permits, inspections, reporting)

- Higher insurance premiums (3-5× baseline rates)

- Greater liability concerns

- Expensive disposal (£5-20 per liter)

- Infrastructure costs (specialized storage, ventilation, safety equipment)

Weak Acids:

- Lower operational costs

- Standard equipment suitable (glass, plastic)

- Basic training (£100-300 per person)

- Simpler regulatory requirements

- Lower insurance costs (standard rates)

- Reduced liability

- Lower disposal costs (£0.50-2 per liter, often can neutralize and drain)

- Standard laboratory infrastructure sufficient

Cost Analysis Example: